Customer Classification in a Data-Driven Utility Landscape

The confluence of energy, customers' needs, and data reshape the way utilities serve the people behind the meter.

Posted From: New York, New York, United States

Customer Energy Series: Article #1

Topics covered:

Energy’s importance in our world

Customers of utilities: who are they, how are they classified, and what do they want?

The current impact of customer classification on utilities and my role

Core to modernity: energy powering our world

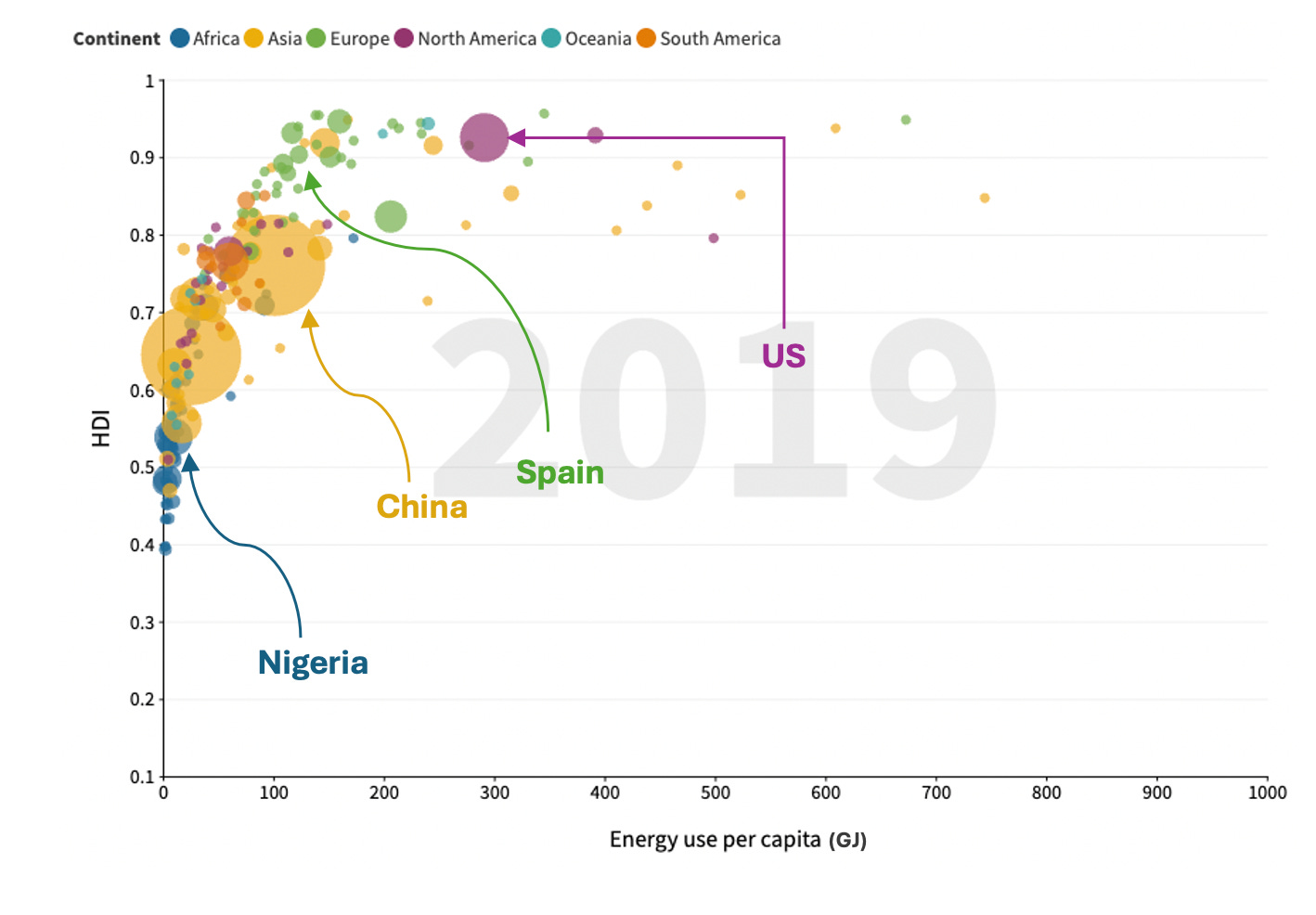

Study after study after study links higher energy use per capita with higher human development index scores (HDI).1 The greater the energy use of an individual within a society, the more likely they are to be living a higher quality life. Modernity rests on the foundation of increased energy use per person.2

Humans consume energy from a variety of sources. The EIA publishes a handy chart each year showing how energy is both consumed and used by different sectors throughout the US.

Energy powers how we live:

Fuels our vehicles (transportation - cars, trucks, planes);

Heats and cools our homes and workplaces (residential + commercial);

Powers factories to produce society's goods (industrial), and;

Fertilizes our land to produce our food (industrial).

Each of these end-use sectors relies on a distinct mix of energy sources. For example, the chart above shows that petroleum (oil) provides a total of 38% of the US energy, with 70% of it going to transportation. Related, transportation derives 89% of its energy use from petroleum (i.e., gasoline and diesel for our vehicles).

Who are utility customers?

But first, what is a utility?

A utility is a “business organization performing a public service and subject to special governmental regulation.” A customer of a utility is the entity that pays the bills for the service. The most common utilities provide electric, gas, and water services. Sometimes, the same utility provides all services in a given area (ex: MLGW in Memphis), sometimes a different entity provides each to the same location.3

How are customers classified?

As a consultant for utility companies across the US, I have to understand a utility’s business so I can best advise them on potential improvements.4 As soon as I hear about my next potential client, I embark on an exploration to become as knowledgeable as I can (as quickly as I can) on their business. I read their company website, a history of their corporate activities, and the news for their latest activities. In addition, I read through their published financial and regulatory material, like their 10-K, FERC, and EIA filings. Each form has a distinct purpose: for instance, the EIA 861 filing breaks out a utility's customers into four classes: Industrial, Commercial, Residential, and Public infrastructure.

Take my home utility of ConEd in New York. Their electric customer classes are found below:

Why do utilities break out their customers into distinct classes?

First, because the EIA requires them to.

Second, because the way the utility assigns costs is partially based on the size and load of a customer.5 Customer classes cause different costs to a utility. A residential apartment like mine consumes, on average, a total of 100 kWh a month.6 Additionally, I incur minuscule demand charges.7 The costs I incur the utility for my energy and demand use are very different than the Holland Tunnel (public infrastructure) down the street from me that consumes thousands more kWh a month at much larger demand charges. In turn, the Holland Tunnel pays a different “rate” for the electricity it consumes than my apartment.8

As shown in the graphic below, customers across utility classes have distinct energy usage characteristics. While residential customers make up 83% of ConEd's total customers, they consume only 33% of ConEd's total energy load. Conversely, Industrial customers make up 16% of ConEd's total customers, yet consume over 63% of ConEd's total energy load.

So, what do customers classes each want? (an introduction)

It is easy to understand that my household energy needs differ from the Holland Tunnel. Yet, they also differ from my aunt who lives a subway-ride away in the Bronx, the church down the street from her house, and the neighborhood Italian bakery in between her apartment building and the church.

Under state law, utilities must serve each of these customer classes.9 Before the rise of digital + data strategies in the past couple of decades, a utility could not reasonably adjust their service to different customers anymore than ensuring that each customers' general service needs were met. So as long as power supply and the quality of power remained stable, the utility had few other opportunities to offer customers increased value.

But no longer.

The proliferation of interconnected devices and their associated data streams allows for utilities to incorporate customers as a core component within their strategy and operations.

Our customer examples from earlier illustrate this well. My needs as a highly-involved energy household are different than my aunt's, the church's, the bakery's, and the Holland Tunnel. And, all of our needs are not stagnant.

When I travel for work or leisure, my energy needs for my apartment are close to non-existent; so long as my food does not spoil, I am good with whatever it takes to reduce my energy bill.

My aunt likely prioritizes energy efficiency, given her oil furnace costs her an arm and a leg each winter season; when she upgrades her 20+ year old unit, her energy needs will evolve as well.

The church is replacing their industrial kitchen and recently updated their HVAC system; their energy needs will change based on price and comfort considerations.

The bakery likely rents their space; as a tenant within a larger commercial zone, they have a split incentive with the owner regarding upgrading the building to improve energy usage.

And the Holland Tunnel, as a critical piece of infrastructure, likely requires extreme resilience to ensure the maintenance of operations.

Example application: ratemaking for the digital age

The ratemaking process has gone on for decades; it forms one of the main bases of our regulatory system, for which the vast majority of the US pays for its energy (electric + gas) costs each month. Created long before the digital and data age, the ratemaking process allowed for “just and reasonable” costs to be recovered by utilities across the customers they served.

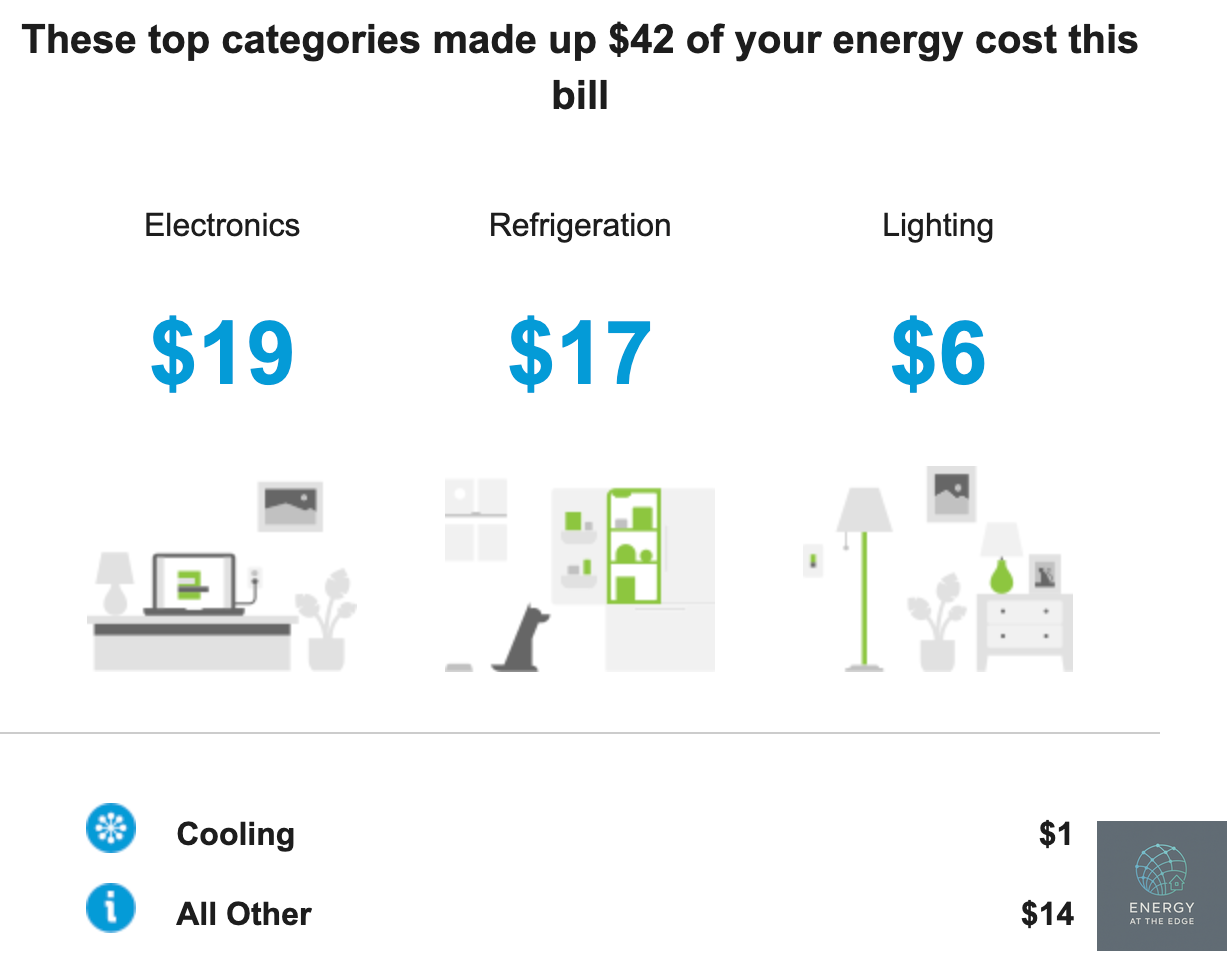

However, decades have passed and our world has changed. Digitialization and the Internet of Things have caused a proliferation of data access points. For instance, smart meters provide a 287,900% more data than standard meters. This allows utilities to better understand a customer's energy consumption. As seen by ConEd below, utilities can use this data to disaggregate a customer’s load to specific categories of use.

One of my roles: advancing utility customer strategy and operations

In my role as an energy transition consultant, one way I advise utility clients is by helping them better understand and serve their customers.

What is the utility’s customer strategy?

More specifically, which customers can provide them the most value, both in reducing cost to serve and increasing their lifetime purchasing value?10

How does the utility achieve their customer strategy?

Should their service process change to better advise customers during outages, or would it be more appropriate to put ever-increasing resources to limiting outages in the first place?

Then, utilities must decide which of these actions are worth investing in and making a reality.

If a new outage service for customers costs $10 Million and will be operationalized in two years, yet another solution that costs 2x as much but will be complete in 1 year can be completed, which option should they pursue?11

In a world where energy enables everything from our morning coffee to critical infrastructure, utilities can no longer afford to treat all customers the same. Utilities who know their customers and act accordingly will deliver superior value to their customers.

In the next post, we will explore what customers actually want across and within customer classes, the value of this segmentation, and if there is a hidden cost to segmentation's insight.

This is post #2 on Energy at the Edge.

Views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of their place of employment.

AI was not used for writing.

Special thanks to Ana M + Adam C for proofreading.

HDI is a measure of the, "average achievement in key dimensions of human development". (Source: Human Development Index | Human Development Reports)

In Brooklyn, ConEd provides electricity, National Grid provides gas, and the New York City Department of Environmental Protection provides water.

How can I offer suggestions without knowing exactly what they do, why they do it and how they do it?

Through the ratemaking process; explained in a primer here.

i.e., total energy consumed.

i.e., the maximum power I consume at one point in time.

The ratemaking process is how utilities assign costs and likewise, make money. It is complex and varies slightly state-by-state; this primer provides an overview for those unfamiliar.

This is completed not by greater consumption of electricity, which regulations disincentivize, but in other methods, such as providing value-added products and services.

This portfolio optimization, and the following product and technology development process, are other ways I help utilities deliver services to their customers.

I am also thinking about how some customers may become prosumers (producing/storing), especially considering the adoption of DERs (to what extent, I’m not sure), but I think it gives utilities another reason to pursue value-aligned and -added opportunities. Perhaps, engaging with these prosumers more actively ...